I went to the Barbican expecting calm. Serene walkways. Brutalist geometry softened by quiet contemplation. A place to wander slowly and feel a little removed from London.

What I found was interesting, absorbing, and occasionally unsettling – not in a bad way, just in a way I had not expected.

I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using my affiliate links.

Outside, the Barbican delivered almost exactly what I had imagined. Even in winter, the garden and terrace felt open and generous. People sat wrapped in coats, coffee cups steaming in gloved hands, lingering rather than rushing. It was not cosy, exactly – more freeing than that. Space to breathe. Space to stay.

Inside was something else entirely.

Note: This wander was focused on the Barbican Centre rather than the wider Barbican Estate, which deserves a visit of its own.

A place to linger – or disappear into

What struck me most inside the Barbican Centre was not the architecture, but the people.

Some were working quietly on laptops, clearly settled in for the long haul, without a coffee cup or receipt in sight. Others were asleep. Not just dozing or resting, but properly asleep. Curled on benches. Slumped in corners. Existing entirely outside the flow of the space.

Later that evening, during the interval of a show, I saw two men fast asleep directly in front of the bar. People queued inches away from them. Glasses clinked. Conversations rose and fell. Nothing disturbed them.

I could not work out why they were there. Were they killing time between journeys? Using the Barbican as a go-between, a place to rest without committing to a hotel? Or was this simply somewhere they knew they would not be moved on?

I never worked out the answer, and that uncertainty was what felt strange. When you go to a show in the evening, you expect an engaged audience – not people existing on an entirely different rhythm.

Not quite serene, but generous

The Barbican did not feel serene to me in the way I had expected. At times it felt more like an airport: a place of waiting, pausing, passing through.

But there was something quietly generous about that.

It is one of the few places in London where you can sit for hours without being asked to justify yourself. You do not need to buy anything. You do not need to perform being a visitor. You can simply exist, whether that means working, wandering, or sleeping through the noise of a busy bar.

That freedom is what makes it fascinating. And also, occasionally, a little odd.

Brutalism, softened by use

The Barbican’s Brutalist architecture is impossible to ignore. Heavy concrete, sharp angles, raised walkways, long sightlines that feel more architectural than human. It is the kind of place people either adore or actively avoid.

From the outside, it feels imposing and uncompromising. I spent a while photographing the exterior, partly because it demands attention, partly because it resists prettiness. It is not trying to charm you.

Inside, though, the building feels softened – not by design, but by how people use it. Laptops balanced on knees. Bags tucked under benches. Bodies folded into corners.

Even out on the terrace, some people chose to sit directly on the ground by the water instead of using the empty tables nearby. Legs crossed on brick, backs against concrete, entirely at ease with the space around them.

The architecture stays severe, but the human presence bends it into something more ambiguous.

It is not warm. But it is permissive.

The things I noticed, but did not do

Part of my time at the Barbican was spent not quite committing to anything.

The food hall looked lively and social, noticeably busier than the quieter walkways around it. It felt like the obvious hub, but I did not go in.

I noticed a separate building housing an art-house cinema, the kind that looks as though it shows carefully curated seasons and old noir films rather than blockbusters. I liked the idea of it immediately, and kept walking.

Upstairs, there were gallery spaces with airport-style security at the entrance. I paused, watched people go in, clocked the atmosphere, and decided not to follow.

The conservatory was closed, and I later learned that it requires advance tickets, released in batches. I signed up for alerts (on the Barbican London website) and left it at that.

None of this felt like missing out. It felt like letting the visit stay loose.

The Barbican London – a lingering contrast

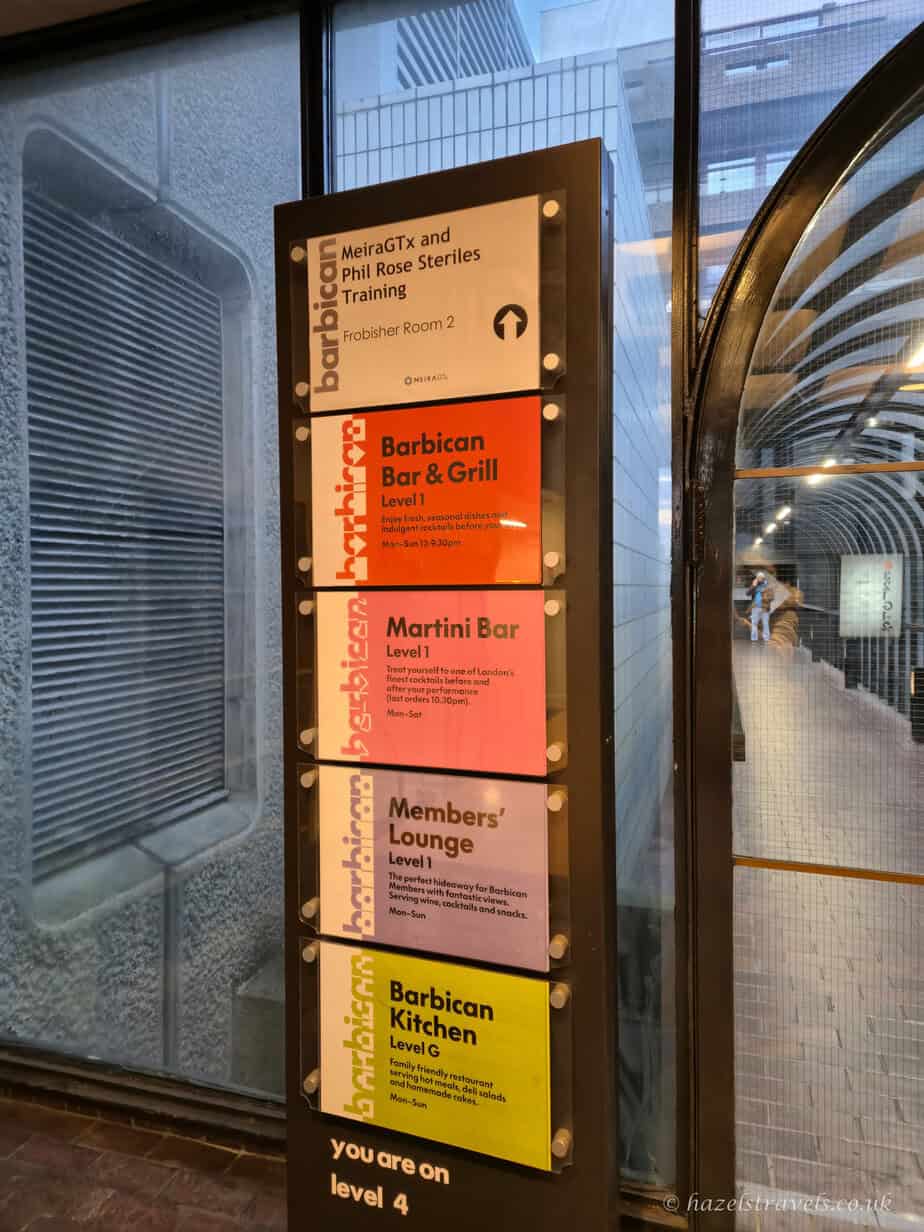

Later, glancing at a floor map, I noticed spaces I had not really registered while wandering: a Members’ Lounge. A Martini Bar. Places that sounded quieter, more refined, and faintly exclusive.

I had not tried to go into any of them. Whether they were genuinely restricted or simply carried that subtle not-for-you energy, I am not sure. But the contrast lingered.

Upstairs, there were signs of curated access and membership. Downstairs, people slept through the noise of a busy bar, worked for hours without buying anything, and stretched out on benches without being asked to move on.

It felt like two different ideas of public space coexisting in the same building.

A place that does not rush you along

What stayed with me most was not any single space, but the overall feeling that the Barbican allows people to linger without expectation.

You can sit for hours without buying a drink.

You can work, sleep, wait, wander.

You do not need to explain yourself.

That is rare in London.

The Barbican London did not turn out to be the calm, contemplative refuge I had imagined. But it was something else entirely: a public building that absorbs people at all stages of their day – and night – without demanding anything in return.

Interesting. A little strange. And quietly memorable.

Save for later 📌

If you enjoy reflective walks, Brutalist architecture, or quieter corners of London, you might want to save this one.

Related reading 🔗

If you liked this reflective take on the Barbican, you might also enjoy:

- What I Learned on a Shoreditch Street Art Tour

- What is Canary Wharf Really Like?

- Things to Do in London in Winter

- Things to Do in Greenwich, London

- 15 Icons of London (and How to Experience Them Like a Local)

These pieces explore London in a similar way – paying attention to atmosphere, context, and how places actually feel when you spend time in them.

👉 Looking for practical travel tools? Check out my Travel Resources page.

Tags: London, UK

Leave a Reply