I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using my affiliate links.

I’ve been photographing street art in Shoreditch for years without fully knowing what I was looking at.

I recognised certain pieces. I stopped to photograph walls I liked. I walked past the same murals again and again, just seeing them as part of the backdrop. But until recently, I didn’t know who had created them, why they were there, or what I was actually seeing beyond colour and scale.

Taking a guided Shoreditch street art tour changed that completely.

Suddenly, familiar streets were layered with meaning. Walls I’d passed dozens of times slowed me down. Small details I’d never noticed before started to stand out. Even the things I thought I disliked – tagging, stickers, half-peeled posters – began to make more sense once I understood where they came from and what they were trying to do.

The tour was run by The Great Weekender, led by Wesley, who went out of his way to answer every question I threw at him, even as my fingers froze trying to type artist names into my phone in the falling snow.

Side note: I attended the tour independently and wasn’t paid or sponsored to write about it.

This isn’t a definitive guide to Shoreditch street art, and it isn’t a checklist of artists or murals. Street art doesn’t work like that. It changes constantly, gets painted over, tagged, removed, or replaced.

What this is instead is a reflection on what happens when you walk through a familiar part of London with context, and how understanding the stories behind the walls can completely change the way you see them.

Artist names are linked throughout the post. Clicking them will take you to the artist’s Instagram page, where you can see more of their work.

Graffiti, Street Art, and Tagging: What I Didn’t Know Before

One of the most useful things I learned early on in the tour was the distinction between graffiti and street art, and where tagging fits into that picture.

It’s easy to lump it all together. Spray paint on walls. Names. Characters. Big murals. But Wesley explained that there are clear differences in intent, technique, and how the work is perceived, both by artists and by the wider community.

Graffiti, in its original form, is about presence and recognition. Tagging is the most basic version of that. A name, a signature, repeated again and again. Throw-ups sit somewhere in the middle: bigger, bolder, more stylised – but focused on speed and visibility. Wildstyle takes that even further, with complex lettering designed to be hard to read unless you’re part of the scene.

One of the reasons trains became such an important canvas is exposure. A tagged train doesn’t stay in one place. It moves. Your name travels across neighbourhoods, across cities, sometimes across entire regions. Visibility is the point.

That explanation landed harder than I expected, because it felt oddly familiar.

I grew up in Southend, Essex, and when I was younger, tagging was everywhere. It was part of the visual language of the place. Even as a kid, I recognised different tags and knew which ones belonged together, long before I understood who they represented or what they stood for. It felt normal. I didn’t even really think of it as illegal until much later. It was just… there.

Street art, by contrast, often works with permission. It’s planned, sometimes commissioned, and usually created with the expectation that it might last a little longer. Techniques vary widely: spray paint, paste-ups, stencilling, pointillism, tape masking, even carving and sculpting – I saw all of these techniques in Shoreditch.

Once you know what you’re looking at, you start to see the skill and time involved, and you understand why some artists choose certain walls, heights, or surfaces.

What struck me most was that none of this exists in neat categories. Graffiti artists don’t always stay in one lane. Street artists don’t necessarily reject tagging. Some of the same people move between styles depending on the space, the moment, or the message.

Artists Who Made Me Stop and Look

Once I understood more about how street art works, certain pieces began to stand out in a different way. Not because they were the biggest or the most photographed, but because they made me slow down.

One of those was a large black-and-white piece by Phlegm, painted high up on a difficult, uneven wall. It depicted a strange, almost fairytale-like figure moving between tall structures on stilts. The drawing was intricate and delicate, and the longer I looked, the more detail I noticed.

Lower down, the work had been heavily tagged over, but most of the main imagery sat far above reach. That wasn’t accidental. Height can be a form of protection. The piece has weathered over time, but it’s still quietly commanding, and I found myself standing there far longer than I expected to.

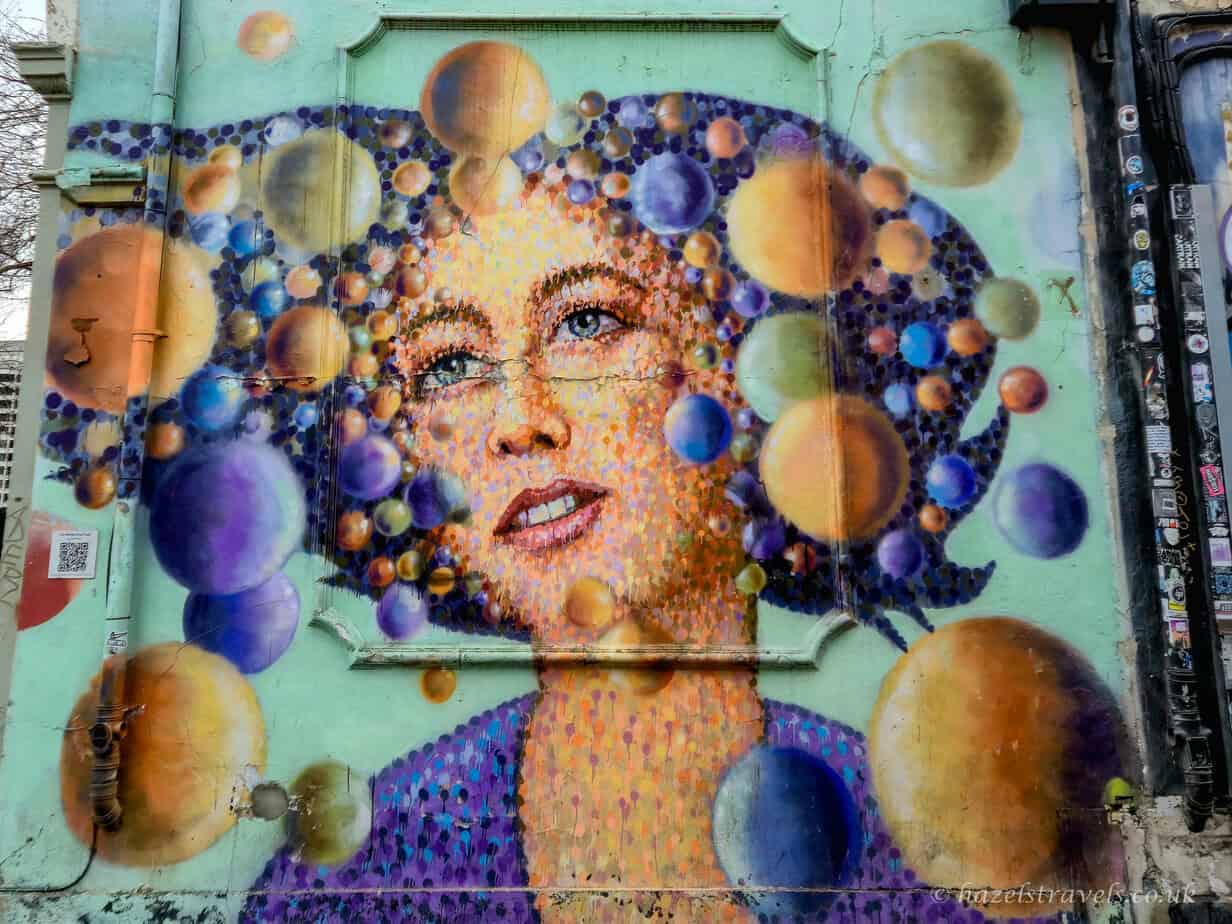

Another artist whose work stayed with me was Jimmy C. I saw several of his pieces during the walk, all using his distinctive pointillism-style technique, where layers of small dots build depth, texture, and movement. Up close, the work feels almost abstract. Step back, and a face quietly comes into focus.

If I had to choose one that lingered most, it would be a portrait of a father and daughter. Not because it was objectively better than the others – they were all excellent – but because it reminded me of a photograph of me and my own father from decades ago.

Seeing Jimmy C’s work in this context helped me understand why it circulates so widely. It’s visually striking without relying on scale or shock, and once you understand the technique behind it, you have to admire the patience involved.

One piece I barely paused at at first was by Dan Kitchener. I recognised it immediately. The rain-slicked street, the neon glow, the reflections of headlights bleeding into colour.

Dan is from the same neck of the woods as me, and I’ve seen his work for years, not just dotted around London but back home too. Because of that familiarity, I think I moved on too quickly. Not because the piece wasn’t impressive (it absolutely was), but because I already knew the visual language so well.

Dan paints everything freehand with spray paint, no stencils, no shortcuts, and the control that must take is extraordinary.

Recognition had quietly replaced curiosity. It took me a while to realise how strange that was, especially given how much I genuinely admire his work. It reminded me how easily we can rush past work we already recognise, even when it’s exceptional.

Another moment came with a much simpler work by Stik. Two stick figures holding hands, one wearing a hijab. On paper, it sounds almost too minimal, but in person, it stopped me in my tracks. There was a tenderness to it, and a sense of intention that didn’t need explanation.

One of the most technically impressive pieces I saw was by Fanakapan, whose hyper-realistic helium balloons rely entirely on painted reflections, rather than metallic paint. Once that was pointed out, it was impossible to unsee the precision involved.

And then there were the moments of outright surprise. Meeting the artist known locally as the Broccoli Man (Adrian Boswell) was one of them. His broccoli sculptures are absurd, funny, and oddly memorable, popping up in unexpected places.

Stepping briefly into his workshop, hearing how the idea started, and seeing how something so strange had taken on a life of its own was a reminder that street art doesn’t have to be serious to be meaningful. Sometimes it just has to exist, insistently and joyfully, in public space.

One of my favourite pieces of the day was also one of the newest, by Louis Michel. It’s a large turkey, painted in vivid, psychedelic colours against a green background, its feathers filled with patterns and unexpected details. The message from the artist is that turkeys are not just for Christmas.

Snow was falling as we stood in front of it, which only heightened the sense that this was a fleeting moment. It might be gone in weeks. It might be painted over. But for that afternoon, it felt electric.

What all of these pieces had in common wasn’t fame or recognisability. It was the way they demanded attention once I knew how to look. Context didn’t make them better in an objective sense, but it made my experience of them deeper.

The Discomfort of Loving Something That Won’t Last

It can be difficult to come to terms with how temporary street art really is.

Some pieces had already faded. Others had been partially painted over or tagged across. In places, finished murals sat alongside layers of stickers and posters, peeling and overlapping until it was hard to tell where one thing ended and another began. At first glance, some walls just looked vandalised. It was only when I slowed down that individual works began to emerge from the noise.

Tagging played a big role in that discomfort. Intellectually, I understood it better once I’d learned the history and motivations behind it. Emotionally, I still found it difficult to see carefully considered work sprayed over with bubble lettering or quick tags. It felt destructive, even though I knew that for some artists, this cycle is expected and even accepted.

What complicated things further was the idea that impermanence isn’t a flaw in street art. It’s part of the point.

Once a piece is out in public, it no longer belongs solely to the artist. It’s exposed to weather, time, other artists, councils, developers, and chance. Some work is commissioned and protected, designed to last longer. Other pieces are created with the full knowledge that they may disappear within days or weeks.

That realisation made me rethink my own instinct to photograph everything. A photo can preserve a piece long after it’s gone, even if it can never fully capture the conditions it existed in.

Standing in falling snow in front of a brand-new mural, knowing it might not look the same in a month, made the experience feel strangely intimate. You’re not just looking at art. You’re sharing time with it.

Not everything resonated with me. Some of the sticker-heavy walls and app-based projects felt gimmicky rather than meaningful. But even that reaction became part of the learning.

Street art isn’t curated for comfort. It doesn’t exist to please everyone. And once I accepted that, I found myself less inclined to judge and more inclined to observe.

Fame, Hype, and the Banksy Machine

It didn’t take long for the conversation to turn to fame.

Not in a starstruck way, but in a practical one. Certain types of street art spread faster than others, and some artists become household names while others remain known mainly within the scene.

This is where the conversation inevitably brushes up against Banksy.

Banksy’s name carries enormous weight, but not always in a way that benefits the wider scene. His work attracts crowds, media attention, and sometimes protective measures that other artists never receive. At the same time, his presence can eclipse everything around it. Murals by lesser-known artists get walked past, photographed without attribution, or ignored altogether because people are scanning walls for a signature style they already know.

What struck me wasn’t whether that attention is deserved. It was how the hype reshapes the landscape. Street art stops being about discovery and becomes about recognition. The thrill shifts from noticing something unexpected to ticking off something familiar.

Many fans of street art are more interested in the artists whose names weren’t already circulating endlessly online. The ones experimenting with technique. The ones choosing difficult walls. The ones creating work that might never go viral but still transforms the street it’s on.

Context Changes Everything

It occurred to me that most street art’s power lies in its anonymity and ephemerality, but fame can quietly work against both. The more a piece is hunted, mapped, and monetised, the further it drifts from the conditions that made it interesting in the first place.

I started spotting things I would never have noticed on my own. Small sculptures perched high above eye level (thank you, Jonesy). Subtle alterations to street signs (thank you, Clet Abraham). Pieces placed in so-called “heaven spots”, painted dangerously high up where removal is difficult and visibility is guaranteed (looking at you, Best Ever). Without someone pointing them out, I would have walked straight past.

Even familiar streets felt different. Walls I’d photographed before now carried backstories. Large collaborative murals I’d seen as purely decorative revealed layers of intention once I knew multiple artists had contributed their own interpretations. What had once felt like visual noise started to organise itself into something closer to conversation.

It also made me more aware of my own role as a photographer and writer. I’ve spent years documenting street art instinctively, drawn to colour, scale, or composition without always understanding the culture behind it. But now I understand these images don’t exist in isolation. They’re part of networks of people, places, histories, and tensions that aren’t always visible at first glance.

Seeing Shoreditch Differently

By the end of the tour, my way of seeing Shoreditch had shifted.

I wasn’t trying to memorise names or catalogue walls. I was paying attention to relationships – between artists and surfaces, between fame and anonymity, between permanence and loss.

Street art doesn’t ask to be permanent. It exists in public, at the mercy of weather, time, councils, developers, and other artists. Some of what I saw will already have changed. That doesn’t make documenting it pointless. It makes paying attention feel more urgent.

I’ll still photograph street art when I see it. But now I’ll do so with more curiosity, more patience, and a greater awareness of what I might be missing at first glance.

Once you learn how to look, it’s hard to see the city the same way again.

You might also enjoy:

London in January: What It’s Really Like (And What to Do).

Where to Stay in London (Areas and Hotels)

How to See Street Art at Santa Maria Street, Funchal (Madeira).

Save to Pinterest

Save this for a slower wander through Shoreditch, or for a day when you want to look at the city differently.

👉 Looking for practical travel tools? Check out my Travel Resources page.

Tags: Art Travel, London, Reflective

Leave a Reply